The UGA School of Social Work Magazine of Transformative Action

ge

RESEARCH

EDUCATION

$16M

SOCIAL INNOVATION

Externally funded research expenditures in FY23

55% 5-year research growth

620 Students in 4 degree programs:

102 BSW • 467 MSW • 30 MA MNL • 21 PhD 8300 + alumni & growing ...

202K Internship hours of innovative service locally, nationally & internationally

Research, education, social innovation: A collective vision for a better future.

1964 2024

Years of Social Impact

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023

Dean:

Communications : Jennifer Abbott, Sam Cook, Kat Farlowe, Johnathan McGinty

Writers: Thomas Ehlers, Johnathan McGinty, Lindsey Ranayhossaini, Joe VanHoose

Copy Editors: Sam Cook, Johnathan McGinty • Design/Layout: Kat Farlowe

Photographs: Adobe Stock Images; Bob and Dawn Davis; Wingate Downs; Brittany Girle; Georgia Historical Society; Audra Melton; UGA Photographic Services: Nancy Evelyn, Peter Frey, Andrew Davis Tucker; UGA School of Social Work; Jana Woodiwiss. © 2023 University of Georgia School of Social

The University of Georgia does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color national or ethnic origin, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, genetic information, or military service in its administrations of educational policies, programs, or activities; its admissions policies; scholarship and loan programs; athletic or other University-administered programs; or employment. Inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Equal Opportunity Office, 119 Holmes-Hunter Academic Building, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602. Telephone 706-542-7912 (V/TDD). Fax 706-542-2822. https:// eoo.uga.edu.

1 The UGA School of Social Work Magazine of Transformative Action | Fall 2023 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Dean ................................................2 Social Work Values in Action .........................................6 Breaking Barriers ..........................................................4 Tackling Global Challenges ............................................8 Bridging the Gap .........................................................12 Marking History ..........................................................15 Who Does Your Taxes? .................................................19 Immigration Insights ...................................................22 Giving Back: The Giving Kitchen ..................................28 Responding to the Injustice Within Social Work Field Education ........................................32 engage | The UGA School of Social Work Magazine of Transformative Action Fall 2023

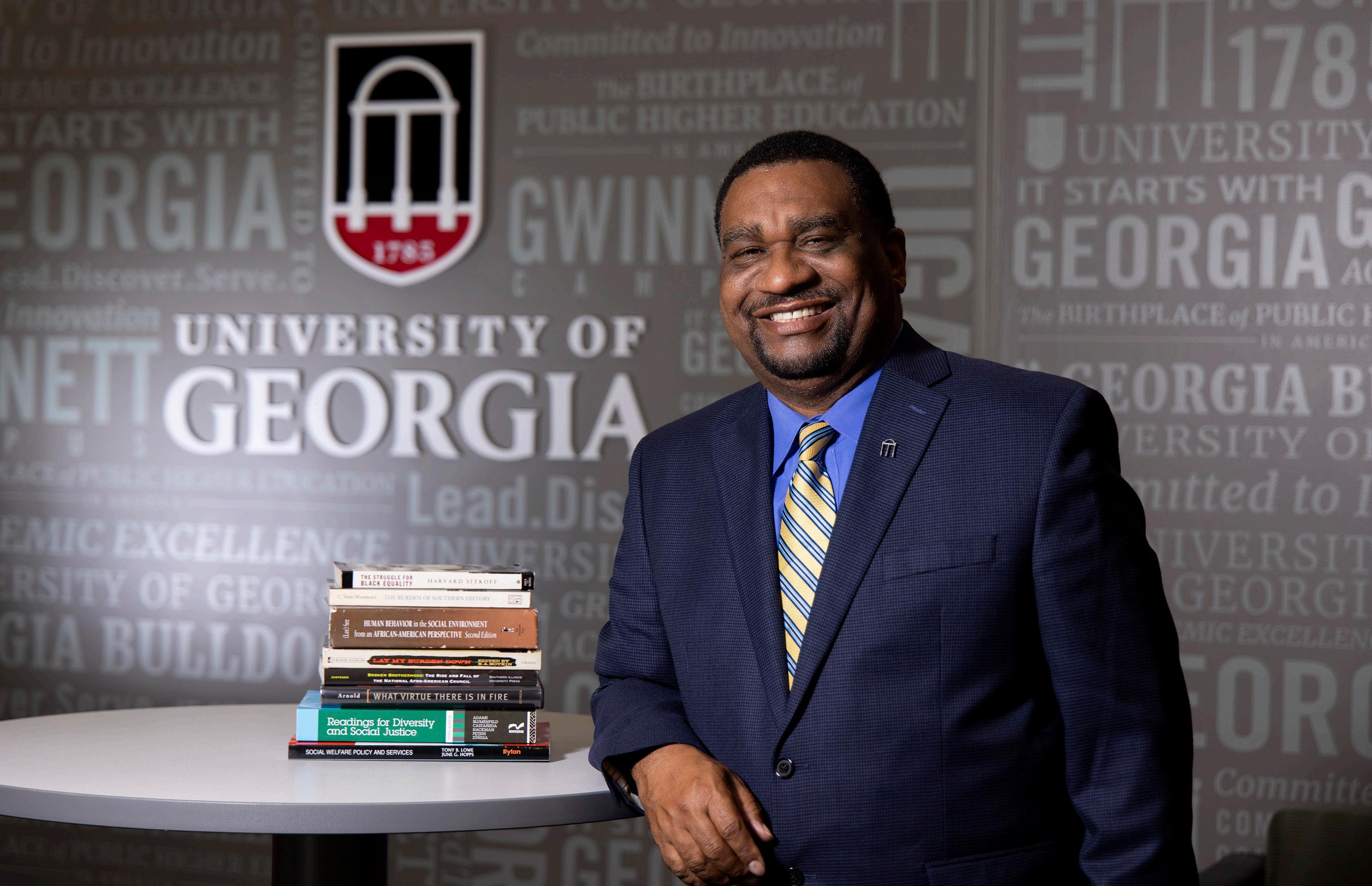

Philip Hong

Work

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023

Welcome from the Dean

On behalf of the School of Social Work at the University of Georgia, I’d like to welcome you to the first edition of Engage, a magazine dedicated to how we are turning the principle of social justice into action. Engage is an evolution of our previous yearly magazine, Social Justice Wanted.

Founded in 2019 by Dean Anna Scheyett, Social Justice Wanted was created out of a period of reflection and co-construction by our faculty in response to the strife and injustices they were witnessing in their communities. Across four issues, the magazine featured thoughtful essays from our faculty and Ph.D. students on topics such as civil rights, human trafficking, domestic violence, disability, historical trauma, and many more. At the core of every issue and every essay was the concept of social justice, the organizing value and beating heart of our field.

Engage magazine takes the spirit established by Social Justice Wanted and carries it out into the world around us. It is about how we’re building bridges with external partners, creating innovative solutions to real-world problems, and engaging with communities locally and globally to work towards a more just and equitable future.

Social justice is not simply an idea, but a call to action. It is a collaborative journey in which we use our expertise, skills, values, research, and practice to create meaningful change. Together, we must build relationships based on authenticity, humility, empathy, and unity under a collective vision for a better world.

When we are rooted in social justice, with a spirit of social innovation, and engaged with our communities, we can create positive, transformative action. I hope you find the examples in Engage inspiring, and support us in our mission.

Dean and Professor

Dean and Professor

2 ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023

Scan or click the QR Code to watch a short video about our vision for a better future!

Wingate Downs

Social Work Values in ACTION

Faculty member Rebecca Wells and MSW/ MPH students worked with UGA’s Archway Partnership and the City of Thomaston to do an asset-mapping project and make recommendations to their community leaders about expanding health and wellness resources.

Part-time faculty member Megan Westbrook’s Community Engagement and Assessment class (SOWK 7236) is partnering with Juvenile Offender Advocates, Inc. to further outreach efforts in the community that will culminate in a community meeting/information session in November.

Members from the UGA School of Social Work and East Athens Development Corporation (EADC) recently met to continue their partnership to address the needs of East Athens residents.

Dr. Llewellyn Cornelius, director of the UGA Center for Social Justice, Human and Civil Rights (CSJ), noted the technical assistance, community engagement and capacity-building efforts that have been done through the joint efforts of the EADC and several UGA schools and organizations.

“It just so happens the agency is an example of what we do outside of off-campus, I would say, locally, regionally, nationally, you know, and so on,” Cornelius said. “What’s important, is that when we think about that phrase social impact, the impact is felt in the communities that we serve. That – in capital letters – that’s what it’s really all about.”

The SSW partnership with HEALTHYouth/Farm to Neighborhood has been awarded funding from an endowment established by Athens native and UGA alumna Bobbi Meeler Sahm. The HEALTHYouth/Farm to Neighborhood program builds sustainable healthy eating habits in elementary and middle school youth by providing nutrition education that teaches hands-on skills, healthy meal planning, and budgeting tips.

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 3

L-R: Rebecca Wells, Ian Marburger, Alexandrea Behler, Alexis Crewse, Destiny Cruz, Fiyinfolu Atanda, Devin Land, Annabel Bunton

L-R: Dean Philip Hong; EADC Executive Director Fred Smith; SSW Instructor and Chess and Community Executive Director Lemuel LaRoche, CSJ Director Llewelyn Cornelius.

Breaking Barriers

Brittany Girle uses her camera to tell stories about the communities she serves.

When Brittany Girle graduated with her BSW in 2004 from the University of Georgia’s School of Social Work, she moved across the country to El Paso, Texas, just two miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. Working for a non-profit organization that built houses in Mexico during the country’s drug war, she got to see the media’s coverage on the situation – and the impact that coverage had on the public.

“Pictures move people,” Girle said. “They get people involved and tell a story.”

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 4 SOCIAL WORK VALUES IN ACTION

Photo: Bob and Dawn Davis. IG @bobanddawn_inthewild

Seeing and believing the power of photos moved her and two close friends to start Photoserve, a nonprofit organization where photographers donate their time and talents to tell the stories of organizations on the front lines of care.

“We’d never heard of the idea to bringing photographers together to give a week of their time to do something good,” Girle said. “You see it with Doctors Without Borders and things like that, they go and serve in different places. So we thought, ‘Why don’t we take people who have a passion for storytelling and give them opportunities in a place where they can really do good, like serving nonprofits.’”

Photoserve takes teams of 8-13 individuals across the world to participate in work projects. Through a mutualistic process, the photographers, who do their own fundraising for the trip, shoot photo and video content, creating valuable footage for the organizations to use. It allows photographers to give back, and many of the trips lead to long-term projects and relationships.

Photoserve doesn’t rely solely on the support of photographers either. Girle will take pretty much anyone, such as a dancer who contacted her and wanted to accompany a team on a trip. The dancer built relationships with the community she served, and she ended up teaching dance to a group on the banks of the Amazon River.

She noted the impact modern technology has on expanding the art and base of storytelling.

“We’re all storytellers at this point,” Girle said. “We all have phones, we all use social media, so we all tell stories.”

When Girle takes groups to serve, her philosophy is different – she makes her photographers put their cameras down. Unlike wedding or professional photographers, Photoserve volunteers don’t shoot

from the jump; instead, they build connections with the subjects in the frames to better tell their stories.

“There’s two ways to take a picture,” Girle said. “You can stand on the sidelines as a journalist and snap it and take a story and go. Or you can really enter in and really connect with a community, and the story you’ll tell is one you’ve experienced – one you’ve entered in.”

Girle’s nonprofit, which has taken trips to provide clean drinking water to Uganda, Puerto Alegria and Fiji and provided for physical needs in Juárez, Mexico, captures moments with the “utmost intentionality and respect” for the individuals and communities they serve.

“Telling the true story and really respecting the integrity of the people that we’re serving, that’s what we really seek to do,” Girle said. “We want to take photographers that have a talent and desire to give back, but we want them to be able to enter into this experience where it can be a mutual situation.”

The organization uses many of the key facets of social work in its efforts. And for Girle, those tenets are something that she realized she utilized in her nonprofit work, even if her professional journey wasn’t as customary as a graduate who went on the clinical side of things.

“Social work is a thing that is used every day in the world, whether that is how we see people, how we connect with them, how we communicate,” she said. “Whether you’re at home now, you’re a parent or you’re working in the business – even if where you’ve gone in your professional life doesn’t look like it’s taken that traditional path – the School of Social Work has impacted who you are and the way you do what you do in your every day.” •

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 6 SOCIAL WORK VALUES IN ACTION BREAKING BARRIERS

Opposite: Brittany Girle shares digital photographs with a woman during a Photoserve project in Uganda. Photo courtesy Brittany Girle.

“Pictures move people. They get people involved and tell a story.”

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 7

Tackling a Global Challenge

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 8

Despite being only a few years old, institutionally speaking that is, the University of Georgia’s Center on Human Trafficking Research & Outreach (CenHTRO) already is making a substantive impact across the globe.

Based at the University of Georgia’s School of Social Work, CenHTRO is a collaborative, cross-disciplinary, and international research hub in the global effort to combat human trafficking. It conducts research, develops programming, and influences policies that drastically and measurably reduce human trafficking and other forms of exploitation.

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 9

It also seeks to address vast gaps in measuring the prevalence of human trafficking worldwide and in implementing evidence-informed interventions. It does so by responding to these disparities by grounding its work in an innovative approach that prioritizes empirical data and, perhaps most importantly, putting a priority on input from survivors of human trafficking.

“Human trafficking is a global scourge that clutches millions of people in its grasp, affecting every country with devastating effects on individuals, families, and communities,” said CenHTRO Director David Okech. “The scope of this issue is clearly dire, but I am not without hope. We rise every day to meet this challenge, encouraged by the mission we have set forth – to reduce human trafficking through research, programs, and policies.”

CenHTRO has employed a multi-faceted approach to tackle this challenge, collaborating with governmental organizations, elected officials, researchers, community leaders and others committed to combating trafficking. In 2022, the organization published three baseline reports focused on Sierra Leone, Guinea and Senegal, giving leaders in those countries the research, data and recommendations necessary to better inform their own efforts.

Across the board, the numbers paint a picture of success. In Senegal and Sierra Leone, more than 1,700 individual police officers, judiciary members, social workers and community stakeholders have been trained on how to identify and address trafficking. And, thanks in part to training efforts like that one, CenHTRO helped to identify 61 new cases of child trafficking, connecting those survivors to necessary support services.

In Sierra Leone, through collaboration with World Hope International, training in trauma-informed care was offered to district-level social workers and community caregivers in an effort to strengthen their capability to aid child trafficking survivors through supportive supervision and mentoring.

Additionally, CenHTRO worked closely with UNODC, the organization’s prosecution partner, to lead a training workshop for local stakeholders in Senegal, including police, magistrates and non-governmental organizations on how best to manage referrals to better assist victims of trafficking.

Embracing innovative methods and strategies is central to CenHTROCENTHRO’s approach. In Senegal, for instance, the Free The Slaves initiative has put an emphasis on raising awareness by better equipping the messengers to the public – the media. It focused on building capacity for institutions of journalism in affected countries in Africa, providing training for 10 members of the media to help them more effectively report on cases of sex trafficking.

Adding on these efforts, CenHTRO has begun to expand its collaborative efforts into southern Africa, planning new research efforts and programs on labor trafficking in Malawi and Zambia. These efforts are the result of meticulous planning and informed by the ongoing collection of data to guide decision making.

“We are making an impact that is underpinned by rigorous science,” Okech said. “We count ourselves among elite global organizations dedicated to advancing and standardizing human trafficking research.”

For CenHTRO, the global focus on curbing trafficking is rooted in Georgia, where its team members serve on various boards and committees and the organization seeks to improve outcomes for survivors and train the next generation of researchers and program specialists. These initiatives receive support from the University of Georgia, as well as the organization’s primary funder, the U.S. Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons.

These efforts to combat trafficking span six countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America, featuring the world’s preeminent prevalence

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 10 TACKLING A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

estimation researchers who are improving the science of how we measure and understand human trafficking in its various international contexts.

Though much work remains for the dedicated team at CenHTRO, Okech knows its lofty ambitions can be fulfilled by continuing to embrace collaboration and cooperation.

“We must continue to assemble all sectors of society – from the village to the boardroom – to combat this scourge,” Okech said. “This includes everyone. Your involvement is necessary if we are to end human trafficking. Only by working together can we achieve such a necessary goal.” •

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 11

CenHTRO Director David Okech and Associate Director Lydia Aletraris photographed at the International Labour Organization headquarters at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, in February 2023. Photo: https://bit.ly/48EQcmy

BRIDGING THE

GAP

Grant allows Social Work team to evaluate Day Reporting Centers

The dynamic between law enforcement and social work has always been rather sensitive, but the work by Orion Mowbray, associate dean for research at the University of Georgia School of Social Work, has helped to bridge the gap between these two worlds.

Three years ago, Mowbray and a team of researchers and students completed a comprehensive analysis of Georgia’s Day Reporter Centers (DRC), a series of facilities that provide programming and services to assist various people on parole or probation who are dealing either with substance abuse issues or were incarcerated due to a drug charge.

That work resulted in the development of a comprehensive assessment tool to better evaluate the DRCs and produced a series of substantive policy recommendations aimed to streamline and improve service delivery at the centers.

This analysis of DRCs is required every three to four years, and earlier this summer Mowbray and his team received another grant from Georgia’s Department of Community Supervision (DCS) to conduct an updated evaluation. As they did previously, the $535,000 grant allows for them to visit the more than 35 DRCs across the state to better understand the challenges and needs of each facility.

L-R: Orion Mowbray, Anna Scheyett, Ed Risler, Michael Robinson, Jeff Skinner. Photo by Wingate Downs.

L-R: Orion Mowbray, Anna Scheyett, Ed Risler, Michael Robinson, Jeff Skinner. Photo by Wingate Downs.

While the team has to redo its evaluation, it also has to be mindful and redesign elements of the process based on changes made by various DRCs throughout the past three years. Last fall, they focused on pilot testing to make sure interviewers were asking the right questions, enabling the team to identify what had changed and how to adapt the program.

“In many of the more rural DRCs, there have been significantly more partnerships with other organizations in the community,” Mowbray said. “For example, many DRCs have developed or improved their relationships with local tech schools and community colleges to provide additional education and workforce development opportunities.”

Collaborating with Mowbray from SSW for this year’s evaluation are Michael Robinson, associate professor and co-PI; Anna Scheyett, professor and co-I; Ed Risler, professor emeritus; Jeff Skinner, project coordinator; and Oluwayomi Paseda, Ph.D. student at SSW.

During the last analysis, Mowbray said his team was able to show that DRCs that scored higher on the evaluation tool prepared by UGA tended to have better outcomes for their participants. These outcomes included fewer positive drug tests and individuals moving through the program faster.

The team also provided three key recommendations to DCS that centered on enhancing service offerings and better aligning various elements of record-keeping and patient care. For instance, the assessment process for program participants varied from facility to facility, which led the UGA team to suggest the development of a uniform assessment tool that could be easily accessible.

Another key recommendation focused on improving coordination between services, such as job training or educational offerings. Most

of those were provided through a collaboration with a technical college or other third-party partner, but many of those agreements were informal. As such, Mowbray suggested formalizing these arrangements through memorandums of understanding and other more official agreements.

The team also recommended that programming like family support services and aftercare support be enhanced.

Mowbray said the partnership between the SSW team and the leadership and staff at DCS has been a positive, constructive one, offering learning opportunities for both sides. It enabled them to break down those perceived barriers between law enforcement and social work and foster better collaboration that yields better results for DRC participants.

For instance, SSW has a data-sharing agreement with DCS, enabling the team to look at other research questions aside from the evaluation component. In the last study, Mowbray’s team was able to produce two publications from that gathered data, something DCS was very supportive of.

As they work through the ongoing evaluation, Mowbray’s team already is seeing the benefits of their initial work.

“All of the DRCs we have been to this year have made changes to their programs as a result of the work we did three years ago,” Mowbray said. “Many of them have focused on improving mental health counseling, their partnerships with public mental health service providers and improving access to vocational training for participants. It’s clear our work is making an impact, which has a direct benefit to the participants attending DRCs.” •

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 14 BRIDGING THE GAP

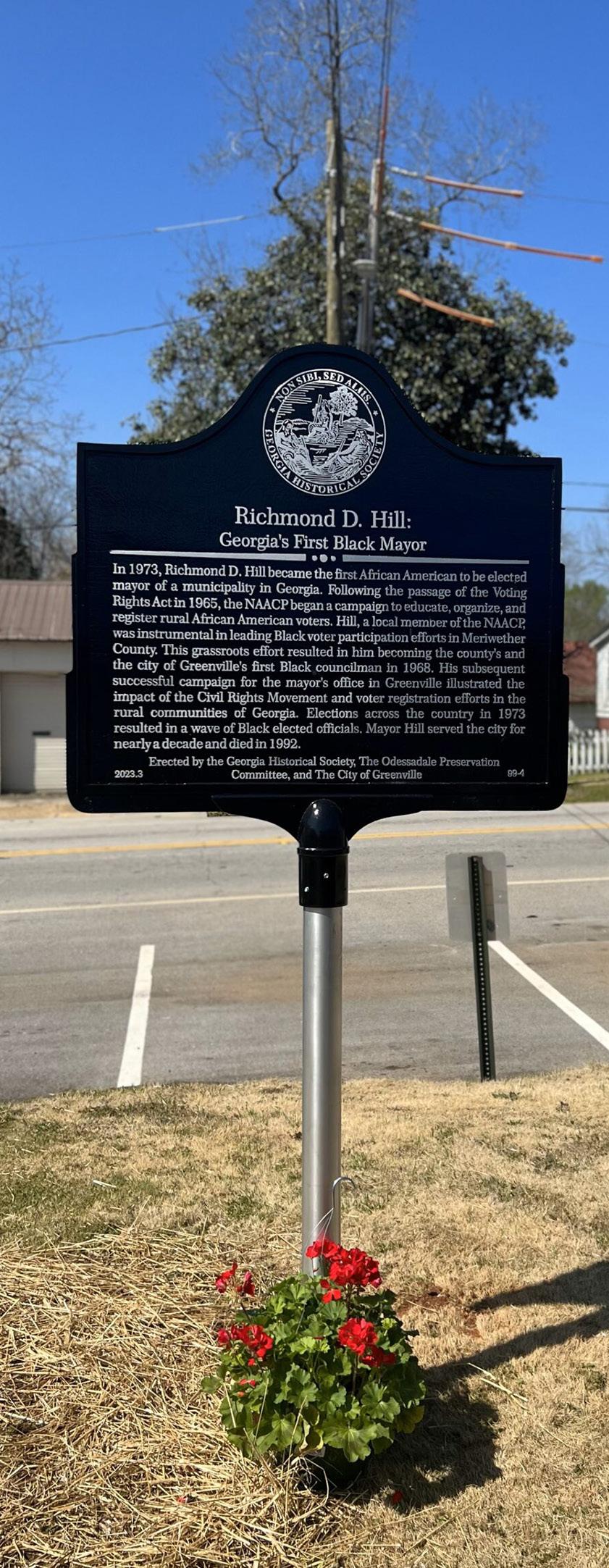

MARKING HISTORY

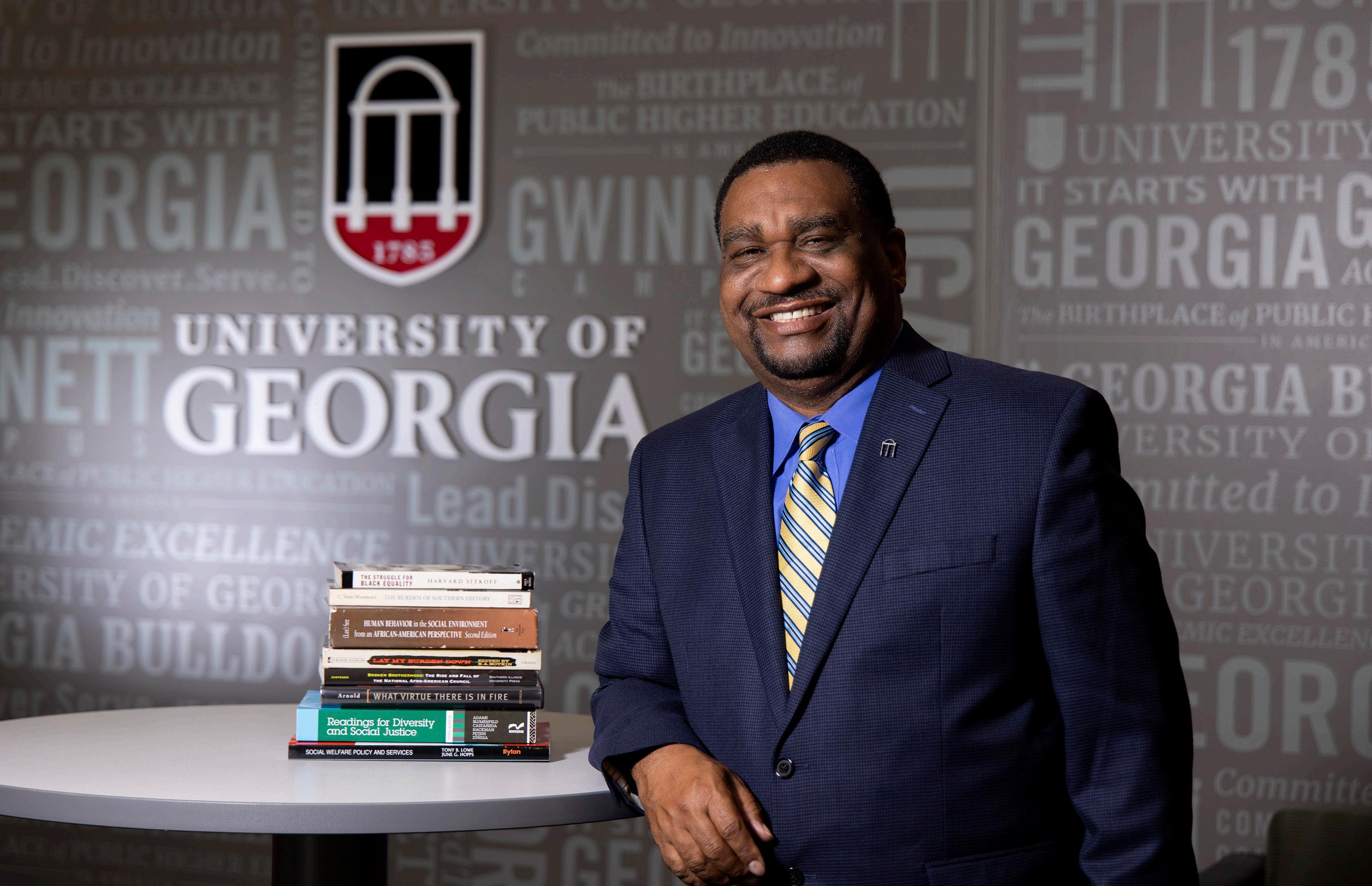

Tony Lowe leads the effort to establish a historical marker in Meriwether County honoring Georgia’s first Black mayor.

An application for a historical marker may have brought Tony Lowe to Meriwether County, but it was the conversations with the people in the community that ultimately led him to make a deeper investment in the project’s success.

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 15

Andrew Davis Tucker

Working with Odessadale Preservation Committee (OPC), Lowe, an associate professor at the University of Georgia School of Social Work, provided the necessary insights and counsel to support the efforts of a passionate group of citizens around a marker recognizing the first AfricanAmerican mayor in Georgia.

Lowe, who had previously helped the city of Hogansville dedicate a marker about Isaiah H. Lofton, understood the process of applications and registrations to get a site awarded. He was already working with the OPC for an application for the Odessadale Elementary School, a Black schoolhouse built around 1909 that was dedicated to Black self-help and education during the times of state-sanctioned racial segregation.

One conversation with Virginia Hill, daughter of the late Richmond Hill, led to a change in plans.

“While we were working on the school project, we were having little side discussions,” Lowe said. “She (Virginia Hill) told me the story that her father was the first African American mayor in Georgia. I grew up in Hogansville, Georgia, which is 15 miles away. I was baffled that I didn’t know this, and this happened in my own backyard.”

The anecdote was enough for Lowe to double his workload. The groups began work on two applications for historical markers – one for the schoolhouse and another for the election of Richmond Hill. Through research, Lowe learned more about Hill’s story.

Hill’s history

Born in Harris County in 1905, Hill was an insurance agent and entrepreneur, founding Hill’s Funeral Home Inc. in 1945. He was a charter member of the Meriwether Chapter of the NAACP and a member of the Rust Chapel United Methodist Church. Lowe found that Hill had been elected to the Greenville City Council in 1968 – the city’s first African American elected to that particular office –before he was elected mayor in 1973.

Lowe explained that Hill’s legacy has been understandably overlooked due to the election of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first black mayor. While Both Hill and Jackson were elected in the same year, Jackson’s election went into a runoff election, while Hill won his election for mayor outright and, as a result, was the first elected Black mayor in Georgia.

“The fact that Maynard won it in Georgia, in Atlanta, the national attention, the national media sucked all of the air out of the room on Mayor Jackson, and Richmond Hill became a footnote to history itself,” Lowe said. “He was forgotten as the Maynard Jackson story was covered widely in The New York Times and all over the country. (Hill’s) story was kind of swept under the rug. That revelation was interesting for me.”

Hill’s and Jackson’s elections were a turning point in the state, which spurred from another moment in Civil Rights history – Rev. Primus King’s successful lawsuit in 1945 that challenged all-white primaries in Columbus is widely recognized among leading scholars as initiating the modern Civil Rights movement, explained Lowe.

Virginia noted the only thing that mattered to her father was serving the citizens of Meriwether County.

“I don’t think it made much difference with my father – he knew that he got in there first – but he accepted it,” Virginia Hill said. “He figured he was mayor of this little town of Greenville, Georgia, that was his main concern, not necessarily being the first African-American for the state of Georgia.”

And he did put in work for his constituents. Lowe noted that Hill challenged the notion of “the other side of the tracks” and worked to provide asphalt roads and plumbing to all parts of the community, particularly those in Black areas without access. He also worked with the state’s senators in Washington D.C. to bring a $1 million funding package to Greenville.

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 16

MARKING HISTORY

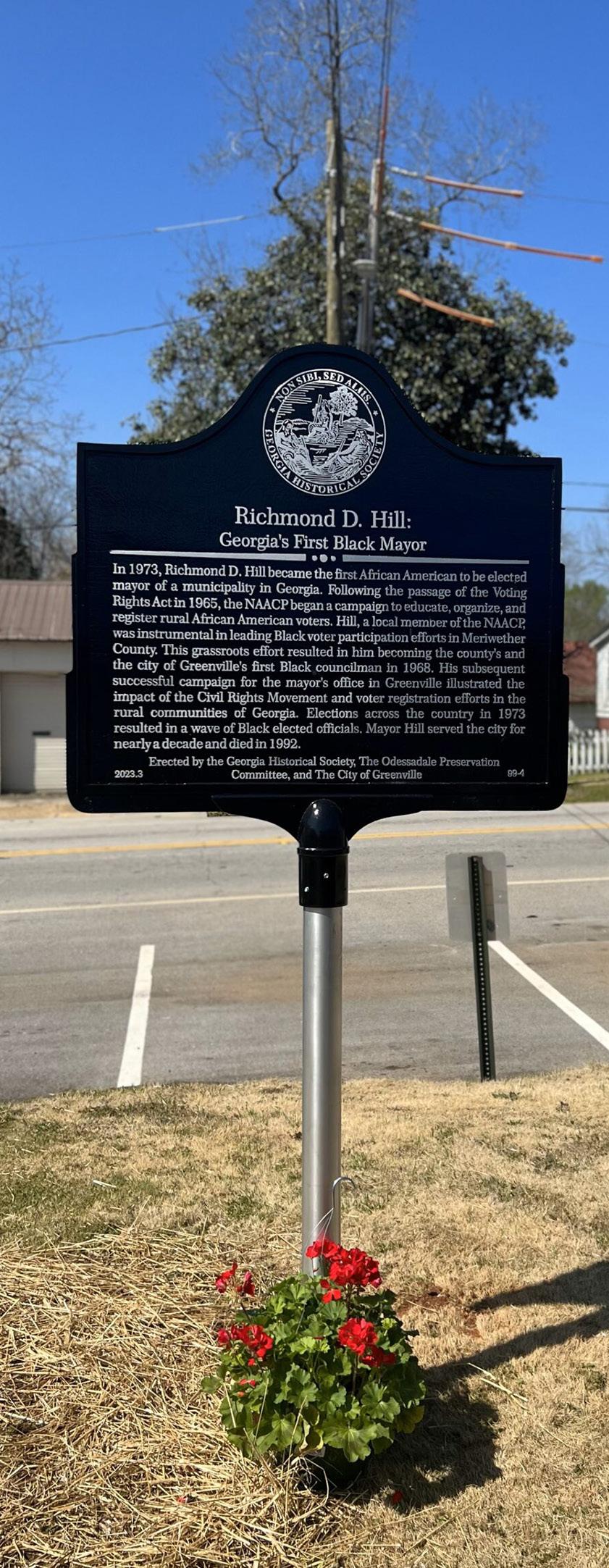

MARKER TEXT

Richmond D. Hill

Georgia’s First Black Mayor

In 1973, Richmond D. Hill became the first African American to be elected mayor of a municipality in Georgia. Following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the NAACP began a campaign to educate, organize, and register rural African American voters. Hill, a local member of the NAACP, was instrumental in leading Black voter participation efforts in Meriwether County. This grassroots effort resulted in him becoming the county’s and the city of Greenville’s first Black councilman in 1968. His subsequent successful campaign for the mayor’s office in Greenville illustrated the impact of the Civil Rights Movement and voter registration efforts in the rural communities of Georgia. Elections across the country in 1973 resulted in a wave of Black elected officials. Mayor Hill served the city for nearly a decade and died in 1992.

Photo: Georgia Historical Society. https://bit.ly/45msU28

Photo: Georgia Historical Society. https://bit.ly/45msU28

At first, both marker applications were rejected. The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) left feedback for Lowe and the committee about the Richmond Hill project and wanted it submitted again. The edits were made, and the application was accepted for the Richmond Hill project, while the Odessadale project received a marker from a private donor unrelated to the GHS.

“Being an academic, you are looking for the right project, the right story itself,” Lowe said. “I knew his story was the right story. I knew his story would be far more attractive to the Georgia Historical Society, and it proved to be true.”

Marking the mayor

Today, the marker stands at Greenville City Hall, funded by the GHS and the Meriwether Chamber of Commerce. It became one of the more than 50 markers in the Georgia Historical Society’s Civil Rights Trail, a collection that focuses broadly on the economic, social, political and cultural history of the Civil Rights Movement in Georgia.

On March 25, a ceremony was held to dedicate the marker. What started as a stormy morning gave way to a sunny ceremony, which included speakers from the city, OPC, family and friends. Individuals representing the various groups with which Hill was affiliated were in attendance, including the NAACP, his church and even members of the Georgia Funeral Service Practitioners Association, an organization the late Hill served as president at one time.

“It was a soul-stirring day, event and occasion all wrapped up into one,” Virginia Hill said. “It floored me that (Lowe) would step up and take it this far. I was very grateful for what he did. Words can’t really describe it – it was just a very high moment for me and I hope for Greenville, too.”

Social work in action

For Lowe, this project was a way to represent UGA as a consultant to local communities.

“This project for me is about marrying the relationship between the University, research and public service,” Lowe said. “This is the public service piece of what we do. We argue the University sits on three pillars – teaching, research and service. This project speaks in a lot of ways to all of those.

“From a teaching standpoint, it gives me an additional body of information to teach from as I look at social justice issues, social policy issues, what have you. From a research standpoint, researching the needs, publishing articles about it. From a service standpoint, as you engage with local communities and engage in civic advocacy itself – that’s what it is, social advocacy. This is really the University engaging communities and being of service to communities, and I believe that is an important piece.”

Virginia, who took over the funeral home, sees the marker as a tribute to her father.

“It’s just humbling to look over to where it is located next to city hall and see where others will come looking,” she said. “For him to be a part of the Civil Rights trail in the State of Georgia – that’s great. It’s very, very humbling.” •

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 18

MARKING HISTORY

Dr. Tony Lowe makes remarks at the unvieling of the historical marker. Photo by permission.

Who Does Your Taxes?

Volunteer tax program led by UGA professors and students offers filing help to those who need it.

EADC VITA help center volunteers. L-R: Addy Bone, Lazarus Nabila, Taylor Nicholson, Tony Mallon, Nyeisha Thompson, Andre Re (community volunteer). Photo by Wingate Downs.

EADC VITA help center volunteers. L-R: Addy Bone, Lazarus Nabila, Taylor Nicholson, Tony Mallon, Nyeisha Thompson, Andre Re (community volunteer). Photo by Wingate Downs.

Tax season regularly brings headaches for many Americans.

It can be trying as families wait to see if Uncle Sam will be taking a little more than they had planned, particularly for those who can’t afford to lose it.

A group from the University of Georgia’s School of Social Work – along with some financial planning students from the College of Family and Consumer Sciences – is doing its part to help keep dollars in the pockets of low-income Athens families.

Anthony Mallon, a clinical associate professor and director of the Institute for Nonprofit Organizations, helps coordinate the UGA Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program, an initiative that, in this iteration, connects students with families in need of help when it comes to filing their taxes. Nationally, the program returns around $65 billion to working families, according to Mallon.

One major part of the VITA program is promoting the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a credit available to both individuals and married couples that earn income under a certain threshold, an option many low-income families are unaware of.

“What happens many times is that people aren’t aware that they are eligible for this,” he said. “If they are lower income, they may not file their taxes or, if they do their taxes and don’t have knowledge of these different credits, they don’t apply for the credit and don’t get it.

Not only does that leave families without money, but the local community suffers.

Between $5 million to $15 million goes unclaimed in Athens-Clarke County every year, according to statistics from UGA FACS. Unlike families with

higher, more disposable incomes, low-wealth families spend a greater portion of their total income on food, gasoline and their children which stimulates the local economy more than a higher wealth family saving theirs.

“That’s less income coming into their household, and it’s also less income coming into their community,” he said. “Part of our goal with this project is to both increase the awareness of this Earned Income Tax Credit and increase the awareness of these VITA sites so that people who could use some assistance – we can provide it for them.”

People of all ages, races and ethnicities make up the diverse group of clients, with some filing jointly while others file single. This diversity is similar to the different people social work students will come in contact with during their careers.

Three sites are located in the Athens area, with one placed at the East Athens Development Corporation (EADC). The EADC offers several services to low-income families, like a Youth Literacy Program, Emergency Food Assistance, Job Coaching and Placement and VITA. The public response is positive.

“We haven’t been collecting any kind of survey data, but anecdotally people are extremely happy that this service is being brought into the community,” he said. “Taxes can be very intimidating, but the ability to come into a nonprofit kind of eases their anxiety. They generally feel comfortable, like they are treated with respect. Even though the service is free, they feel comfortable that volunteers have been trained by the IRS.”

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 20

VITA TAX ASSISTANCE PROGRAM

Ken Chrzanowski, manager of business development for Georgia United Credit Union (GUCU) and a member of the Board of Advisors for the School of Social Work, has helped coach students since the program began at UGA in 2006. Over the years, the program has grown from 133 individuals seeking help in the first year to filing 1,832 federal forms in 2022, totaling more than 36,600 returns during its life.

“The most impactful part of it to me is knowing that the people who need the financial help the most are getting it free of charge,” Chrzanowski said. “This program simply helps people. There’s no other motive – it’s just there to be a good community partner.”

The numbers prove the program’s help. Since 2006, the program has helped individuals receive more than $24.5 million in federal tax refunds and $4.2 million in state tax refunds, according to Chrzanowski.

The program ran partially out of a GUCU branch until growth and other factors forced it fully to the Charles Schwab center on UGA’s campus. On campus, students are able to meet with individuals throughout the day, instead of after-work hours and weekends. In 2019, the program introduced a virtual option, allowing individuals to fill out forms remotely. VITA’s flexibility has been important to its growth, according to Chrzanowski.

“It’s just changed over time,” Chrzanowski said. “That just adds to the capacity.”

With thousands of sites across the country, the VITA program offers more than just tax help. Built around service, if individuals need help in other areas, like job placement or filling out financial aid paperwork for college, information on other nonprofits or service organizations can be given.

“The taxes are what brings people in,” Mallon said. “But if we identify other needs, we can link people with other resources, which I think is a real bonus.”

At the beginning of the program every year, students are often nervous and intimidated by preparing taxes, but after working with clients, they grow a sense of confidence through working as a team and end up enjoying the experience, according to Mallon.

“Students are surprised how much taxes are relevant to their broader educational experience,” Mallon said. “What they find is when someone comes to them for tax assistance, there are typically other issues that they are in need of.

“The social workers have grown a greater appreciation for the relevance of tax preparation for their career and understanding the needs of low-income families.” •

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 21 VITA TAX ASSISTANCE PROGRAM

Ken Chrzanowski, manager of business development for Georgia United Credit Union and a member of the Board of Advisors for the School of Social Work. Photo by Wingate Downs.

I mmigration Insights

by Jana Woodiwiss

“Family separations are pivotal moments in the lives of everyone involved. I know because I’ve felt it firsthand.”

Iwas adopted from San Salvador, El Salvador during the 1980s. This was a tumultuous time for the country as it was in the middle of a civil war. My adoptive parents provided me with opportunities I could never dream of within the context of the destruction faced there. On the flip side, I lost my biological family, culture, and language -- all of the things that made me feel on the inside like I look on the outside. I struggled with that into adulthood. My adoption and recently being reunited with my biological family play a large role in the work I do today.

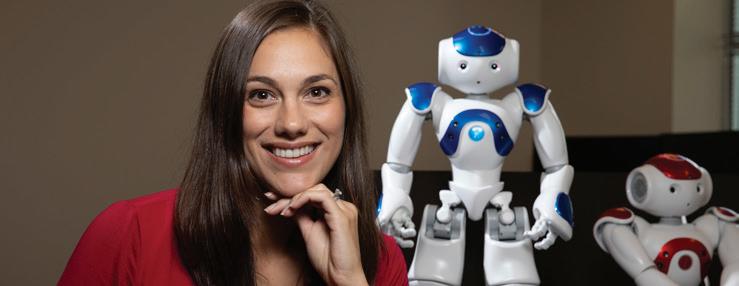

Inspiration for the trip came from my time with Dr. Jenay Beer, associate professor holding a joint appointment at the School of Social Work and College of Public Health. In her Fall 2022 Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) class, she challenged students with the question, “How are agencies benefiting from the research you are conducting with them?” My research with an agency in South Georgia named El Refugio immediately came to mind. El Refugio is a 501-c3 nonprofit organization that assists immigrants at Stewart Detention Center (SDC) and their loved ones through hospitality, visitation, support, and advocacy.

I reached out to my colleague Patti Ghezzi, Development and Communication Coordinator with El Refugio and asked the question, “What does El Refugio need?” She asked about getting student visits to the agency started again, which had ceased following the COVID-19 pandemic, and we agreed to explore getting a group together soon.

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 23 IMMIGRATION INSIGHTS

Ph.D. candidate Jana Woodiwiss, MSW, LMSW. Photo by Laurie Anderson.

A few weeks later at the 2022 Council of Social Work Education conference in Anaheim, California, I connected with Dr. Jane McPherson about resuming trips for students down to El Refugio and SDC. SDC, run by the private corporation Core Civic, is a medium-security detention center housing immigrant detainees facing charges from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The facility houses more than 1,700 individuals, and it has grown a reputation for being one of the most dangerous centers in the nation when factoring illness, death rates, and human rights violations.

School of Social Work faculty and students had made trips to the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga. before the COVID-19 pandemic, and I wanted to revamp the effort and give students the opportunity to visit El Refugio and learn about the agency, detention center, family separation and the economic impact of detention centers on local communities. Dr. McPherson was onboard, and she invited me to guest lecture

in her International Social Work class to discuss detention, deportation, and pitch the trip.

The next order of business was obtaining funding. I initially sought funding from the Office of ServiceLearning with the SL Support Grant, which provides $500 to support activities related to developing, implementing, or expanding academic service-learning opportunities for UGA students. Unfortunately, our project did not qualify. Next, I met with Dean Phillip Hong and other members of the SSW and presented our trip proposal. Dean Hong approved and funded our proposal to visit El Refugio and SDC. Additional funding for the trip came from the University of Georgia Women’s Club, via the Dianne C. Davidson fellowship I received last summer.

Two masters-level students from the School of Social Work helped with logistics and communication for the trip. George Harrison Shu, co-president of Students for Global Social Work and Shelby Lopez, who hosts an online podcast

IMMIGRATION INSIGHTS

SSW students pose with Woodiwiss outside the El Refugio Hospitatlity House. L–R: Maeve Breathnach, Sydney Sanders, Woodiwiss, Juwon Johnson, Jalynn Colvin, Alexis Tuggle, Surafel Tesfaye. Photo courtesy Jana Woodiwiss.

about immigration raids titled Solo Eramos Ninos with her husband Angel Lopez.

Between the weekends of February 18 and February 25, 2023, we took two dozen students to El Refugio and SDC. Each group made the threeand-a-half-hour bus ride each way to meet agency volunteers and hosts at the El Refugio guest house.

The first trip was hosted by El Refugio long-time volunteers Marilyn McGinnis and Holly Patrick. We took a closer look at the facility’s history, its impact on the community and the politics surrounding it. They were able to share intimate first-hand experiences of working with families separated from their loved ones and the social and economic challenges that were the fallout from their absence.

The second trip was hosted by El Refugio’s Board Chair, PJ Edwards and his wife Amy. PJ has never met a stranger and has more knowledge about detention and deportation in the United States than anyone I have ever met. After the lesson, we were able to walk around the Lumpkin town square. It was a ghost town. Shops abandoned and ravaged encircled the town’s courthouse. At first glance, we just thought these businesses were closed due to it being the weekend, but upon walking up to the buildings we could see they had not been used in quite some time.

Every student saw the layout of the facility, along with a line of vans that move detainees from the facility to airports if they are deported. They experienced the hyper security and surveillance indicative of prison. El Refugio’s webpage has an excerpt that hits home when describing the effects of the present immigration system: “detention steals the dignity of immigrants.” Loss of family, security, legal rights and information regarding their own cases are an experience that accompanies the horrific environment they left in their home country and perilous journey to request asylum they had already faced. This – the SDC -- is their welcome.

Due to certain limitations at SDC – including a limited number of telephones to speak with detainees and the need to speak fluent Spanish – only three of the 24 students were able to actually speak with individuals incarcerated; this number we hope to increase in future visits. Those students, however, were able to share what they learned from detainees with the group and made for great discussion to reflect on and process on the long rides back.

Individuals that were detained shared their struggles, like unknown court dates, inability to speak with family members and poor facility conditions. All factors that can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression as outcomes of their stays there. One top of those issues, those detained are housed in pods with other individuals facing a variety of charges. Many are only facing charges for

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 25 IMMIGRATION INSIGHTS

Abandoned businesses in Lumpkin, GA. Photos by Jana Woodiwiss.

“El Refugio’s webpage has an excerpt that hits home when describing the effects of the present immigration system: ‘detention steals the dignity of immigrants.’ Loss of family, security, legal rights and information regarding their own cases are an experience that accompanies the horrific environment they left in their home country and perilous journey to request asylum they had already faced. This – the SDC – is their welcome.”

lacking proper documentation but are housed with the few population members high-risk charges.

After the trip, students shared what they learned and experienced – like seeing immigration from a family perspective, a lens gained through conversations with El Refugio volunteers. Others were able to relate the history of immigration with for-profit detention centers, contemplating the impact of these centers on communities economically and socio-demographically.

Students learned about human rights abuses that can, and do, happen during detention, such as forced labor. The irony here is that many individuals enter the United States with economic interests of working hard and earning a fair wage for their families, but are then sent to detention centers where they are paid a couple of dollars for work they are doing.

On top of informative talks, students found ways to stay connected with El Refugio by writing letters or volunteering with the guest house or agency.

This experiential learning trip helped students gain detailed knowledge about the impacts of immigration detention and deportation they may not have otherwise had. The partnership between the UGA School of Social Work and El Refugio is invaluable, and it is my hope that it will continue to grow and ensure trips annually for students. It is also my hope that the UGA Service-Learning Program will consider future applications for funding trips like these with the SL Grant.

I would like to extend a huge “Thank You” to the UGA School of Social Work’s Dean, Dr. Phillip Hong, for largely funding the trip. Another thanks goes out to the University of Georgia Women’s Club, which put up the rest of the funds for the trip. Your generosity informed two-dozen students

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 26

Photo by Audra Melton. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/4bHEJnM

about current issues, inspiring them to make a difference.

In addition to funding, many thank yous go to: Patti Ghezzi, PJ Edwards, Marylin McGinnis, Holly Patrick with El Refugio; George Harrison

Shu and Shelby Lopez, students at the UGA School of Social Work; Dr. Jane McPherson, Dr. Jenay Beer, and Christina Autry with the UGA School of Social Work; and Gayle Noblet with the University Women’s Club.

It takes a village, and this was mine in making this trip a reality!

Not only did the trip impact students, but it also impacted the lives of people being detained and their families. Part of the trip’s cost also included a small honorarium for El Refugio’s time, space, facilitation, and educational instruction during both visits. These funds allow the agency to continue their various programs.

The visits help keep agencies serving immigrant families alive, allow help to enter through the guest house doors, keep students connected and further serve a community that sees numbers of victims at the hands of a for-profit detention center.

It is my hope that this trip continues, and the School of Social Work focuses educational opportunities on immigration. As students experience this trip, see the center’s conditions, and speak with volunteers and the people being incarcerated, it creates the memories needed to fuel the consistent and ongoing change that is the mission of our work. •

Link to Shelby’s podcast, Solo Eramos Ninos: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/solo%C3%A9ramos-ni%C3%B1os/id1663686890

Link to El Refugio: https://elrefugiostewart.org/

IMMIGRATION INSIGHTS

El Refugio supporters protest outside the Stewart Detention Center.

Photo retrieved from https://bit.ly/3T668bF.

Giving Back

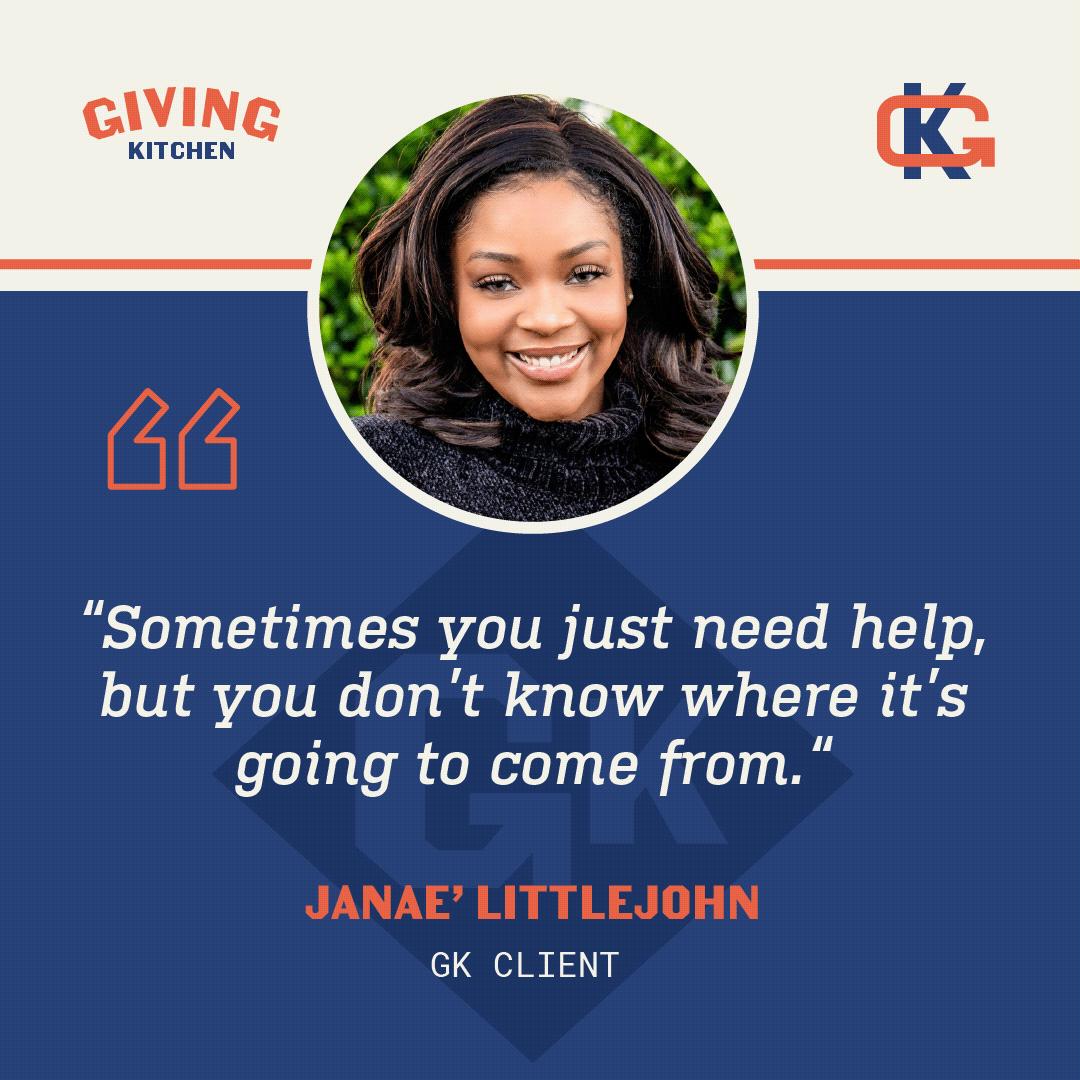

Brian Schroeder and Giving Kitchen provide emergency services to food service workers in need.

When Bryan Schroeder is in charge of the kitchen, his go-to menu changes with the company.

For a smaller crowd, he’ll go for a homemade pizza. A low-country boil for a larger one.

Schroeder doesn’t do much cooking for the Giving Kitchen, the non-profit he is the executive director of, but he helps people who do.

Giving Kitchen seeks to provide emergency assistance to food service workers who work in restaurants, catering, concessions, food trucks and more through a host of support measures.

Financial resources that cover rent and utilities are given to those with injury, illness, family deaths or housing crises up to six months after the crisis occurs. Additionally, a network of community resources, like connections to legal, financial or immigration services, help for substance abuse or addiction and resources for physical health and wellness are made available to those in need.

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 28

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 29

MA NPO alum Brian Schroeder with his golden retriever Miles. The Giving Kitchen earned the James Beard Foundation Humanitarian of the Year Award for 2019. Photo by Peter Frey.

Schroeder received his Master of Arts in Nonprofit Management and Leadership (MA NML) in 2006, acquiring the tools to lead non-profits successfully. For Giving Kitchen, he’s done just that.

The numbers don’t lie. Since its inception in 2013, Giving Kitchen has paid for 475 years of rent for those in need, serving more than 11,500 clients –including 3,215 children – while awarding $7.66 million in aid through more than 4,500 awards. It has responded to calls for help from 43 states, staving off utility disconnection in 76.6% of those receiving awards while preventing eviction for

Mallon said the program has around 30 masters students, with a total of 200 students in classes to complete a master’s degree or certificate program. The certificate program provides opportunities to undergraduates, master’s students or individuals looking for a standalone credential. While Schroeder graduated before Mallon took over the program, the latter said he is a great example of what the program stands for.

“I think Bryan and the Giving Kitchen epitomize non-profit leaders who are innovative and creative, see a need in the community and work with the

more than 3,200 clients. Just last year, Giving Kitchen awarded $2.13 million to nearly 3,000 clients.

Formerly the Master of Arts in Nonprofit Organizations (MNPO), the MA NML program started in 2000, associated with both the Schools of Social Work and Public and International Affairs. Today, the program, housed in the Institute for Nonprofit Organizations, is headed by Anthony Mallon, hosting two full-time and a half-dozen part-time faculty.

community to develop effective solutions,” Mallon said. “In our program, which is housed in the School of Social Work, we emphasize the concept of mutuality, the idea of working WITH communities. For example, we don’t just say, ‘Hey food service workers, here’s what WE think you need;’ rather our alumni work to really understand what their clientele needs and then to develop programs and services that are based on community-identified needs.”

The organization was named to the Bulldog 100 list for 2023, and also was tabbed for Fast Company’s

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 30 GIVING BACK: GIVING KITCHEN

https://thegivingkitchen.org/

Source:

“Brands That Matter” list. Keeping clients at the center has led to much of the success that Schroeder and the Giving Kitchen have found, and led to growth for the organization and its reach.

“We went from three people around a table to 25 at our organization,” he said. “It’s an incredible team – some of the best and brightest work at Giving Kitchen. I have no idea if there has been a School of Social Work or MNPO person who has been recognized or honored in this running a business context, but I think that is pretty cool.

“I’m happy to represent the School of Social Work with the rest of the entrepreneurs because I do think that something that social work needs is entrepreneurial leadership and willingness to take risks on the behalf of the people we serve.”

Schroeder has big goals for Giving Kitchen, such as reaching 100,000 people per year by 2030. As the organization continues to grow, he maintains the importance of sticking to the reason it began.

“I think at the end of the day your nonprofit is only as good as its mission,” he said. “It’s understanding your mission and guarding your mission and (figuring out) how do you make it real. The last three years, especially with COVID, was a big test for us – would we pivot from a mission perspective, would we get into types of services where we don’t belong.

“We had to work really hard to stay in our lane, understand where we can have influence. That to me is one of the most important things an executive director can do – you’re only going to go as far as simple and straightforward and direct as your mission is. Not trying to do something for everyone but focusing on what we do best is probably one of the hardest parts of the job but one of the most rewarding things for the company when it comes to what we’ve been able to do and accomplish.” •

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 31 GIVING BACK: GIVING KITCHEN

Excerpts from Giving Kitchen client stories. Source: https://thegivingkitchen.org/pressroom

RESPONDING TO THE INJUSTICE WITHIN SOCIAL WORK FIELD EDUCATION

Field education was named the signature pedagogy of Social Work education in 2008 (Wayne et al., 2010). Before then, field education was the norm in social work programs as early as 1974 (Roberson and Adedoyin, 2019). The benefits of field education are obvious. Field education provides students with a unique experience, where they have the opportunity to practice the skills they are learning in the classroom in the field itself. Additionally, this component of social work education provides students with hands-on experience in the field of social work before they have even graduated. However, there is much to criticize about this component of social work education as it is currently implemented and the social injustices the current systems sustain.

Perhaps the biggest concern of field education as of late has been the lack of payment provided to social work students for their work in the field (Harmon, 2021; Students for Labor Practices, 2022; Metz and Fox, 2022). For example, UGA MSW students devote up to 20 hours a week and 912 hours over the course of their MSW program at UGA to work at their field placement with no pay. Student organizers at UGA conducted a survey in the spring of 2021 examining the hardships of field education among social work students at UGA using closed

and open-ended questions that asked about field experiences, the impacts of field education on one’s paid employment, and the impacts of field education on one’s finances. Our survey of approximately 100 School of Social Work students found that not only do most social work students at UGA have to work for free at their field placement, they also must pay to do so in the form of tuition for their field practicum, student liability insurance, uniforms, background checks, drug screens, and

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 32

Elisabeth Colquitt, MSW ’23

RESPONSE TO INJUSTICE IN SW FIELD EDUCATION

Christopher Strickland, MSW ’18 PhD Candidate (ABD)

other miscellaneous costs required by field sites. This leaves students forced to pay these costs out of pocket so that they can work for free at their field site.

Unpaid fieldwork is a dangerous precedent in the field of social work. While students of social work are being taught the importance of their Code of Ethics and how to apply those ethics to their lives and practice, they are caught in the middle of their field’s own ethical violations by being forced to work for free and suffer financially because of it. According to the NASW Code of Ethics, social workers are obligated to work toward social change to challenge injustices. In fact, we are ethically obligated to direct our efforts toward problems related to poverty and unemployment. Yet, under the status quo of field education, social work students are actively experiencing issues related to poverty and unemployment as a result of the precedent of unpaid field work that the field of social work has set and continues to uphold.

In addition to ignoring our ethical demand to address problems related to poverty and unemployment, the field of Social Work further undermines the professional integrity and longterm viability of our discipline through the norm of unpaid fieldwork. Research has shown that students who participate in paid internships are more likely than students who participate in unpaid internships to receive full-time employment offers post-graduation (NACE, 2016). Additionally, these students also tend to receive a higher salary than students who had an unpaid internship (NACE, 2016).

The unpaid internship framework of field education also violates its guiding ethical axioms by sustaining systems of racism and sexism it has purported to engage and dismantle. While there is a clear difference in employment offers and salaries among students who had paid internships, it is important to note that feminized fields, such as education, social services, and health professions, are less likely to receive paid internships when

compared to male-dominated fields, such as engineering, physical sciences, and computer science (Zilvinskis et al., 2020). Additionally, it is known that women continue to earn less than men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). If one could examine the intersection of gender and unpaid internships on salary differences post-graduation, one could argue that women are being conditioned to accept lower paid salaries through the unpaid internship requirements of their field. With this in mind, it is easy to see how the field of Social Work contributes to the inequality in pay among women through unpaid fieldwork.

In addition to the gender differences seen in salaries, and unpaid and paid internships, racial differences are evident, as well. According to NACE’s 2019 Student Survey (NACE, 2020), African American students are more likely than white students to be unpaid interns. Furthermore, given historically marginalized households earn about half as much as the average White household and own 20 percent as much wealth, it is no coincidence that the social work discipline is overwhelmingly represented by a White demographic that can typically shoulder the burden of unpaid work (Bhutta et al., 2020). Racial disparities are also seen in pay gaps, with Black workers only earning 76% of what white workers earn (United States Department of Labor, 2020). Any institution whose outcomes enable racist and sexist inequities is itself a racist and sexist institution. Even more relevant to our local context, a curriculum reputedly steeped in values of social justice and human well-being framed by an institution built through exploited labor atop stolen land must interrogate how this history continues to seep into contemporary practices.

It is clear that unpaid internships in the field of Social Work support the sexist and racist systems used to further inequity. While internships have been the signature pedagogy of field education since 2008, there has been little success in dismantling the dangerous norm of unpaid field work in social work education by leaders in the

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 33 RESPONSE TO INJUSTICE IN SW FIELD EDUCATION

field of Social Work. However, social work students across the United States have decided to take on this effort themselves by organizing the national movement now known as Payment for Placements (P4P). P4P began in November 2021 by Social Work students at the University of Michigan, and has since grown into a national movement made up of 43 chapters in Social Work programs across the United States. The national P4P movement is calling for all students of Social Work to be paid for the fieldwork that is required of them, while individual P4P chapters across the country incorporate other specific goals into their own local movements.

Interns, received national media attention, and is onboarding new chapters regularly as word of the movement spreads. Individual chapters across the country have also had numerous successes, including the passing of legislation expanding paid fieldwork among social work students, receiving gas stipends for field-related travel, endorsement from state NASW chapters, and developing individual Joint Task Forces with the admin of their individual schools of Social Work.

On a local level, the P4P chapter at the University of Georgia began in the spring of 2022 and has had similar success. Made up of over 120 members, P4P at UGA has gained the commitment of our Dean and an expanding list of faculty and administrative leadership to join our own Joint Task Force on Stipends to explore all possible ways to expand paid fieldwork opportunities for students, and

Since its start in 2021, P4P has gained a great amount of progress in a short amount of time. The national movement has met with the president of the CSWE, received endorsement from Pay Our Source:

ENGAGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2023 34

https://www.payment4placements.org/ RESPONSE TO INJUSTICE IN SW FIELD EDUCATION

to eliminate out-of-pocket costs students face to participate in field education, including student liability insurance, parking, field-related travel, background checks, and more. Recently, P4P at UGA led a school-wide protest against the implementation of Tevera, a program used to track field hours and other field-related data, which would add another financial burden onto already financially exhausted students. P4P was successful in their protest, and the School of Social Work secured funding to cover the cost of Tevera for Social Work students at UGA this academic year. While this movement is new to UGA, students are hopeful that with the current support of the Dean’s office, the Field Education Office, and representatives from its faculty, the School of Social Work can work to expand paid field work opportunities to reduce the inequities in Social Work education.

As bell hooks once noted in her manifesto on transgressive pedagogy, “theory is not inherently healing, liberatory, or revolutionary. It fulfills this function only when we ask that it do so and direct our theorizing toward this end” (hooks, 1994, p. 6, 8). In the abstract, the social work discipline’s prized Code of Ethics projects a discipline poised for practice anchored in social justice, anti-racist, and culturally affirmative practice. But theorizing doesn’t preclude engaging in practice that undermines it. By changing the way social work students are supported through our signature pedagogy by committing to paying them for the value commanded in their field sites, our discipline can begin to direct our grand theorizing to the ends we have prized since the inception of our profession. •

references

Bhutta, N., Chang, A. C., Dettling, L. J., & Hsu, J. W. (2020, September 28). Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 survey of Consumer Finances. FEDS Notes. https://bitchily/45tigGE

Harmon, M. (2021, April 20). MSW students cite unpaid field positions as contributor to financial instability. The Michigan Daily. https://bit.ly/3rKqVa5

Metz, E. B., & Fox, S. K. (2022, March 21). Opinion: Social work students are required to work thousands of hours for free. We demand change. San Diego Union-Tribune. https://bit.ly/3PMlsrc

NACE. (2020, July 24). Racial disproportionalities exist in terms of intern representation. https://bit.ly/3tAXR5d

NACE. (2016, March 23). Paid interns/co-ops see greater offer rates and salary offers than their unpaid classmates

https://bit.ly/3Q9eUnT

Roberson, C. J., & Adedoyin, A. C. (2019). Historical and contemporary synopsis of the development of field education guidelines in BSW, MSW and doctoral programs. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 22(1), 22–27. https://bit.ly/3LYuKz9

Students for Labor Practices. (2022, May 20). We’ve been working hard in the city for free, including on the COVID-19 Front Lines. Baltimore Brew

https://bit.ly/45sNrlD

United States Department of Labor. (2020, July). Earnings disparities by race and ethnicity.

https://bit.ly/3Qnhl6F

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, January 24). Median earnings for women in 2021 were 83.1 percent of the median for men. TED: The Economic Daily

https://bit.ly/3LZ06G2

Wayne, J., Raskin, M., & Bogo, M. (2010). Field education as the signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327–339. https://bit.ly/3PVJ8tc

Zilvinskis, J., Gillis, J., & Smith, K. K. (2020). Unpaid versus paid internships: Group membership makes the difference. Journal of College Student Development 61(4), 510-516. https://bit.ly/3FbmFnd

UGA SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK | FALL 2023 35 RESPONSE TO INJUSTICE IN SW FIELD EDUCATION

The University of Georgia School of Social Work’s primary focus on social justice and diversity, equity, and inclusion in leadership, research, and teaching serve as the organizing principles for all aspects of our programs to train social workers for the 21st Century.

Our mission is to prepare “culturally responsive practitioners and scholars to be leaders in addressing social problems and promoting social justice, locally and globally, through teaching, research, and service.” And our work is guided by the NASW Code of Ethics to advance knowledge, skills, and values of future social workers.

– Dean Philip Hong

At the UGA School of Social Work, we are redefining education in social work, social policy and nonprofit leadership.

WILL YOU SUPPORT THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK?

SCAN THE CODE TO MAKE YOUR GIFT TODAY!

If you have questions about giving to the School of Social Work, please contact Megan Powell, development coordinator, at megafon@uga.edu or call 706-542-5466.

.

BSW • MSW • Online MSW • MSW/JD • MSW/MPH • MSW/M.Div. • Ph.D. MA and Online Certificate in Nonprofit Management & Leadership Certificate in Substance Use Counseling Center for Human Trafficking Research & Outreach Center for Social Justice, Human and Civil Rights Institute for Nonprofit Organizations SSW.UGA.EDU

Photo by Nancy Evelyn

Dean and Professor

Dean and Professor

L-R: Orion Mowbray, Anna Scheyett, Ed Risler, Michael Robinson, Jeff Skinner. Photo by Wingate Downs.

L-R: Orion Mowbray, Anna Scheyett, Ed Risler, Michael Robinson, Jeff Skinner. Photo by Wingate Downs.

Photo: Georgia Historical Society. https://bit.ly/45msU28

Photo: Georgia Historical Society. https://bit.ly/45msU28

EADC VITA help center volunteers. L-R: Addy Bone, Lazarus Nabila, Taylor Nicholson, Tony Mallon, Nyeisha Thompson, Andre Re (community volunteer). Photo by Wingate Downs.

EADC VITA help center volunteers. L-R: Addy Bone, Lazarus Nabila, Taylor Nicholson, Tony Mallon, Nyeisha Thompson, Andre Re (community volunteer). Photo by Wingate Downs.